Chainsaw Chicken first learned he was popular overseas when someone sent him a still image.

It arrived without explanation. No return address. Just an image file and a short line in the email body:

Thought you should see this.

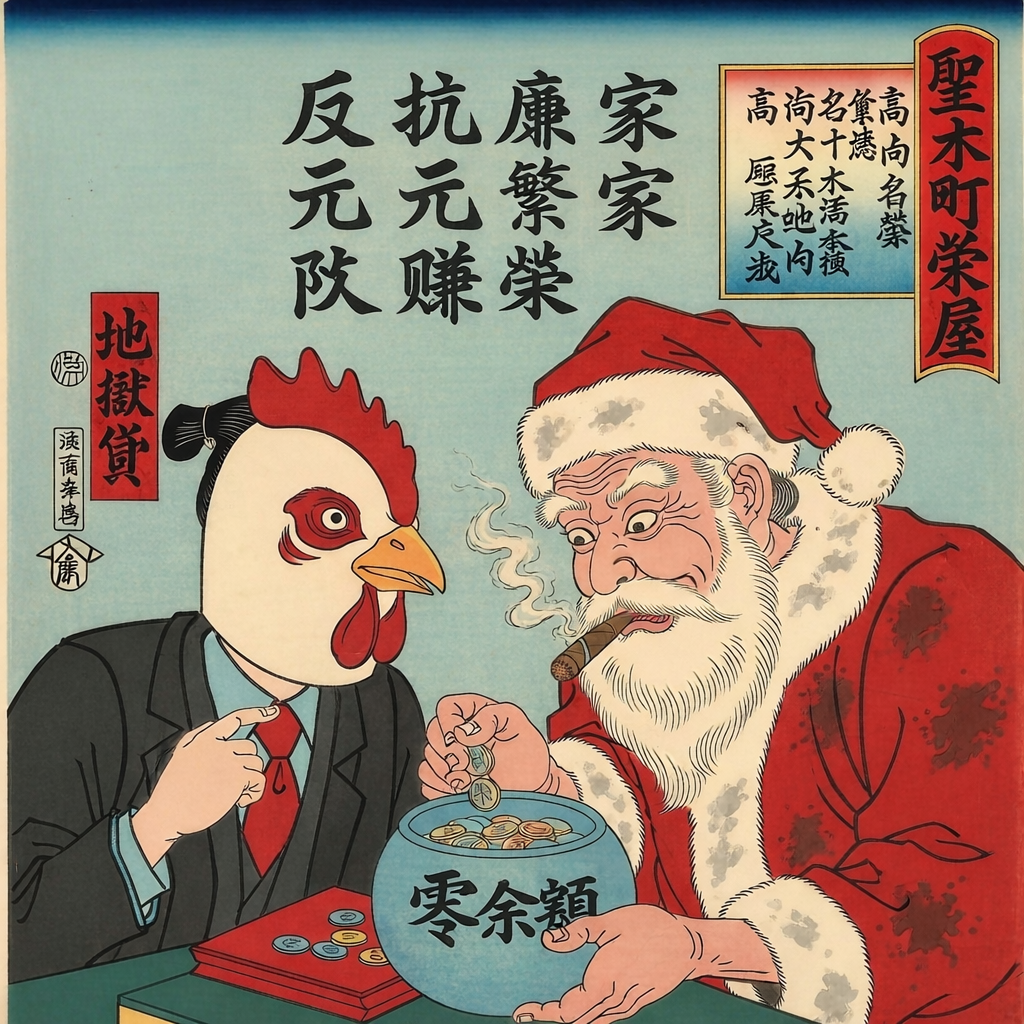

The image showed two figures seated at a table. One of them resembled Chainsaw, though not exactly. The face was wrong in the way foreign cartoons are always wrong — close enough to be unmistakable, but distant enough to deny responsibility. The other figure appeared to be Santa Claus, older and thinner than usual, dropping a coin into a glass jar.

The jar was clearly labeled.

Chainsaw didn’t read Chinese, but he didn’t need to.

He understood zero when he saw it.

At the bottom of the image was a line of text identifying it as a “cartoon.”

Not fan art.

Not parody.

A cartoon.

Chainsaw sat with it for a long time.

He had always assumed popularity would announce itself. A knock on the door. A contract. A polite but firm cease-and-desist. Instead, it seemed to happen quietly, somewhere else, using a different alphabet.

Later, he learned more.

The cartoon was slow. Barely animated. His counterpart blinked once every few seconds. The coin always dropped. The jar was never full. Smoke drifted upward and vanished, as if time itself were getting bored and leaving.

There were no punchlines.

Apparently, this was the point.

Chainsaw was troubled by the accuracy.

They had changed his proportions, simplified his posture, and adjusted his expression to something more acceptable for broadcast. Still, the meaning survived intact. The ritual. The effort. The eternal optimism of adding something to a system that politely refused to acknowledge it.

He wondered how they had gotten that part so right.

Chainsaw considered issuing a statement but decided against it. The cartoon didn’t misrepresent him. It represented what happened after him — what the world did once the idea escaped.

That night, he placed a coin into a jar of his own.

Nothing happened.

Which reassured him immensely.